Faces detection with caffe

#Convolutional Neural Network

##Introduction The aim of our project was to create a convolutional neural network (CNN) to determine if a small image of 36*36 is a face or not, with caffe (machine learning framework). In a second time, and once the CNN was trained, we had to create a tool using it to detect faces in any image.

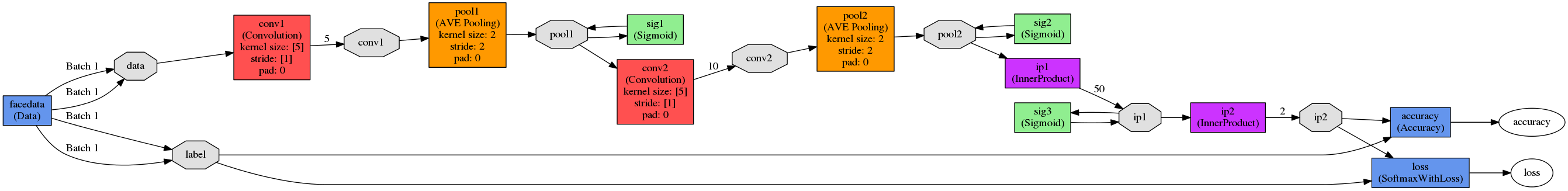

##Architecture We used a simple one, with convolution, pooling, and only two neurons layers (so it is not really “deep” learning). Here is a schema of the architecture :

##First iteration

On our first iteration, testing our CNN on test images (~7600 images) gave us a precision of ~84%, depending on our luck

because the training of the CNN is not deterministic. It was decent.

##First iteration

On our first iteration, testing our CNN on test images (~7600 images) gave us a precision of ~84%, depending on our luck

because the training of the CNN is not deterministic. It was decent.

To detect faces in a picture, we used a slippery window of 36*36 that we applied on each part of the image (with a step of 5px), and extracted this 36*36 image to check if is a face or not, thanks to our CNN. Moreover, each time the slippery window end the image, we resize it with a factor 0.9, in order to detect bigger faces than 36*36. This process worked quite good actually :

As you can see, most of faces are detected, but some non-faces are also detected. In addition, we had many detections, and our goal was to detect faces with just a single square or a single circle per face !

##Second iteration

To solve the many squares problem, we used a clustering algorithm : DBSCAN. You can read more about it here. In short, it detects highest densities. Here we detected highest densities of

square, and placed a circle on it.

With correct parameters, it was pretty good !

##Third iteration We wanted to increase our detection precision. First we tried to change our architecture, but it was not very concluding.

Then, we tried to add a bootstraping step in the creation of the CNN. The principle is as follow:

- We create a big set of images of non faces : 36*36 images extracted from textures images

- We train our CNN like before.

- We make it work on textures we extracted on the step 1, and select images that are detected as faces with a threshold of 0.9. In fact, we choose images where our CNN makes big mistakes.

- We train our CNN again, but now we add the non-faces from the previous step to the training set. We take caution to have as many faces as non-faces in the training set.

- We lower the threshold.

- We go back to step 3, until the threshold value is 0

The advantage of bootstraping is that we train the CNN to better separate faces from non-faces. The fact that we first take into account big mistakes makes the CNN more performant, just like when you teach to a children, you first make him correct his big mistakes, not subtles errors.

With this approach, we manage to reach a precision of 93.3% !

Here are some results :

It does not seems so much better on this image than in the one from iteration 2, but trust me the detection is way better on other images.

Here we can se that Daryl (on the right) is not detected because his face is a little turn away from the camera, and our training only included faces “in front” of the camera. In the same way, I think black faces may be more difficult to detect for our CNN because there was less black faces in our training set.

##Improvement axes We could keep only one circle when there are multiple on a the same location. A more important and reprensentative set of faces could also be a good improvement. Finally, we did not pay attention to performances, we could optimize the process because actually, it takes something like 30 seconds to detect faces in an image, depending on it size.

##Bonus : Frankenstein Part of what makes Convolutional Neural Networks so powerful is the large quantity of data you “feed” them with during the learning phase. Supposing your dataset is diverse enough, the more training images, the better the detection rate in the end. Unfortunately, it’s not always easy to find datasets that are both publicly available and large & diverse enough. Quite by accident we found a very interesting publication 1 adressing the matter. The idea is to merge a set of giver faces into a synthesized face by picking facial features from each and pasting them onto a giver head. For fun, we wanted to see how we could apply this concept and synthesize faces to create a dataset as large as that we were successfully using to train our CNN, and if the results were comparable.

Collect a (relatively) small sample of faces, and synthesize monsters

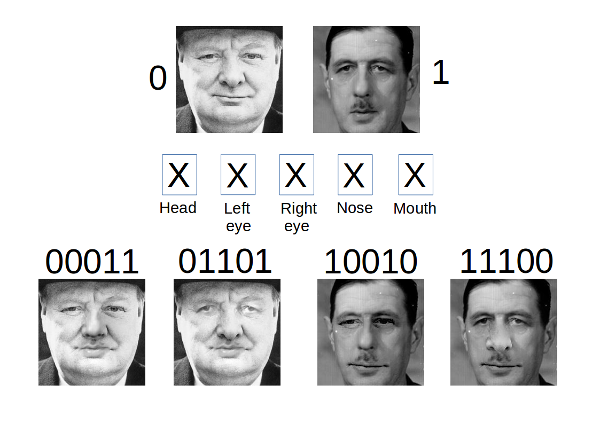

Here you can see an exemple of face synthesis from two faces, using randomly generated binary codes (ranging from 1 to 25-2) to choose which giver to pick facial features from.

To create more synthesized faces, we picked random combinations of four face images from our dataset. For each combination, we created a synthesized face using features from the four images : one face giving the head, one face giving the eyes, another the nose and the last the mouth.

Our goal was to produce approximately 60 000 unique faces. Theoretically, such a number can be obtained from only 37 initial unique faces :

\[\binom{36}{4} = 58905 < 60000 < \binom{37}{4} = 66045\]We used The BioID face database, composed of 1521 images from 23 different persons, which might not really be diverse enough to give the best results possible but had the enormous advantage to include, for each image, the coordinates of facial features, allowing us to skip the feature selection work.

Results

A sample of faces we synthesized from the BioID dataset and used to train our CNN

In the end, we randomly created 60 000 “Frankenstein monsters” using parts of randomly selected faces among the initial 1500 images. With our CNN and using bootstrapping during the training phase, the frankenstein dataset produced an accuracy of 89.4% on our test images - not that bad ! Best results would certainly be achieved with a more diverse initial dataset (I may try that sooner or later, and update this post).

Authors: - BASEILHAC Theo - CACHARD Côme - MATHONAT Romain - NATIVEL Nicolas - NOUVELLET Victor

1 G. Hu, X. Peng, Y. Yang, T. Hospedales, et J. Verbeek, « Frankenstein: Learning Deep Face Representations using Small Data », arXiv:1603.06470 [cs], mars 2016. ↩